PIONEERRESPOND

Henry/Harry Louis MARKER 1876 - 1966

| |

| aka | Henry Louis Marker, Harry Louis Marker, Henry L. Marker, Harry L. Marker, Henry Marker, Harry Marker, H. Marker |

| nationality | |

| occupation | |

| birth | 21 June 1876, Indianapolis, Marion, Indiana (1900 & 1920 CENSUS) |

| remark | not in Hartford, CT, as stated in Harry's obituary |

| baptism | |

| death | 21 March 1966, East Orange Veterans Hospital, Newark, Essex, NJ |

| burial | |

| marriage | married between June 1900 and Aug 1905 to:

(1) Pearl Bessie CHAMBERLAIN (1) Pearl Bessie CHAMBERLAIN b. .... <1881>, ...., PA |

| children | no children |

| remark | divorced after Jan 1920 (Census date) |

| marriage |

(2) Louise ...... (2) Louise ...... b. ..... |

| children | no children |

PARENTS

| father | Steven/Stephen Arnold MARKER b. 27 Aug 1847, Somerville, Butler, Ohio |

| mother | Columbia Alferetta BEAL b. 24 Jan 1858/1859, Kansas City, Wyandotte, Kansas |

| marriage | got married on 5 Aug 1874, Greencastle, Putnam, Indiana |

| children |

|

LIFE

1850 CENSUS (7 Sept 1850, Union, Union, Indiana):

Caleb MARKER (23y; b. Ohio)

Amanda [BOTY] - MARKER (20y; b. Ohio)

- Stephen (3y; Indiana)

1870 CENSUS (10 June 1870, Richmond, Wayne, Indiana):

Stephen Marker (23y; boarder; b. Ohio) saddler

1880 CENSUS (..................):

1920 CENSUS (South Orange, Essex, NJ, January 1920):

Harry L. MARKER (43y) (b. Indiana) Examiner of Phono Records

Pearl MARKER (38y) (b. PA)

1920 CENSUS (6 Jan 1920, Newark, Essex, NJ)

Stephen A. Marker (72y)

[Columbia] Alferetta Marker (61y)

1930 CENSUS (Beverley Hills, Los Angeles, CA, 7 April 1930):

Probably wrong guy, but where are Harry & Louise Marker in 1930 and afterwards?

Harry MARKER (30y; age does not match! Harry was 54y) film editor movie studio

Louise MARKER (30y)

Beverley Hills, Los Angeles, CA

(Louise's civil says: CA!)

recorder COLUMBIA

1906 in Siam (probably must be "1907")

recording in the Far East (NYT 26 Dec 1912 + ELLIS ISLAND)

in 1919 chief recording engineer EMERSON RECORDS (1915-1921)

HARRY LOUIS MARKER (1876-1966)

Harry Louis Marker was born in 1876 in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Footnote: His obituary though has: Hartford, Connecticut.

He was the son of Stephen A. Marker and Columbia Beal-Marker.

Stephen A. Marker (harnessmaker) is listed in the U.S. City Directories, Hartford, Connecticut: 1877, 1880 and 1881

Apparently by 1877 the family had moved to Hartford, Connecticut.

Harry Marker not mentioned in the 1880 Census.

In 1899 enrolled in the "Science Division" of Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, but did not complete his degree (he also played on football team)

Served in Spanish-American War (1898)

Was a 32nd Degree Mason

In 1900 Harry was living in Newark City, Essex, New Jersey and working as an insurance clerk.

1900 CENSUS (6 June 1900, Newark City, Essex, NJ):

Steven (=Stephen) A. MARKER (b. Aug 1847, Ohio) Foreman Leather Factory

Collanbia (=Columbia) MARKER (b. Jan 1858/1859, Kansas)

children:

- Harry L. (b. June 1876, Indiana) Insurance Clerk

- Florence May (b. .. Feb 1878, Connecticut) stenographer

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Columbia

Most early Chinese discs recorded by Columbia were arranged for by J. Ullmann and Co.'s offices in Shanghai and Hong Kong. In June, 1904, to launch a new recording plan by Ullmann and Co.'s offices, Columbia sent Charles. W. Carson, a recording expert from Ohio, to Shanghai. Carson's work was under the direction of a Mr. Stanley, who was then at Columbia's office in San Francisco and later became the manager of the Oakland Branch. Carson's recording program was also arranged by Stanley, the music chosen by Chinese consultants. Columbia sent all of the recording equipment and accessories to Shanghai aboard the S.S. "Coptic", and the shipment arrived in Shanghai that November.

With the equipment received, Carson made recordings of Chinese northern operas in Shanghai until March, 1905, and then recorded Cantonese opera in Hong Kong from April to August of that year. From June 1904 until September, 1905, Carson had spent a total of fifteen months in China, making hundreds of records, but many of them were unacceptable in quality. The Chinese northern operas were issued in a 15000 series with catalogue numbers from around 15500 to 158XX, principally on two different labels. One was with the American flag and Chinese Qing-Dynasty's dragon flag label (Fig.11), and the other was with the name "Ullmann and Co.", the sales agent in China, but in Chinese characters (Fig.12). The Cantonese operas were issued in a 57000 series with catalogue numbers from 57500 to 576XX and the label had a golden Chinese dragon on a red background (Fig.13). Because of problems with masters and grooves, these recordings were not satisfactory to Ullmann. In the meantime, Carson was asked by his headquarters in San Francisco to go to Japan by the first available ship for more recording activity, where he would work together with Harry L. Marker, under the direction of F. W. Horne.

Ullmann

In early 1907, Carson returned to Shanghai to complete his unfinished recordings. I believe that the recordings made in this session were issued in a 60000 series with catalogue numbers from 60000 to 605xx for the Chinese northern operas, with a label similar to those of the 15000 series. Around May, he moved to Hong Kong to be an assistant to Harry L. Marker for a new recording session. Recordings made in this session were issued in a 57000 series with catalogue numbers ranging from 57700 to 578XX, and the labels had a golden Chinese dragon on a green background (Fig.14).

These recordings covered Chinese southern operas, such as Cantonese operas, as well as those from Amoy, Swatow and Hong Kong. Harry L. Marker spent a year, from about May, 1907, in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Beijing and Tianjin. Part of the time he worked with Carson and part of the time he worked alone. Columbia's other recording expert, Charles J. Hopkins, made a globe-trotting trip from Britain in October, 1903, staying in China for about one month in 1904, but he seemed not to have made any recordings at that time.

J.Ullmann and Co.'s offices in Shanghai were located at No. 564 Nanking Road, in Tientsin inside the French Concession and in Hong Kong at 74 Queens Road. All of the recordings cut for Ullmann were sent to the United States for pressing in Bridgeport, CT. by the American Graphophone Company under the direction of T.H. Macdonald. The finished discs were then sent back to China for sale by J. Ullmann and Co., the agent for the Chinese market. The records made in Hong Kong in the 57000 series were of Cantonese and Southern operas, and were targetted to Cantonese consumers in Hong Kong, but also to those emigrees in the U.S., Canada and South-East Asia. Because some were destined for the diaspora market, there was no mention of the name of the Ullmann agency on those labels. Since few in the Chinese diaspora were from northern China, the discs of northern opera were sold only inside China.

(from: The Development of Chinese Records from the Qing Dynasty to 1918 by Du Jun Min (Buenos Aires, Argentina) on website: Antique Phonograph News (Canadian Antique Phonograph Society))

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

From Talking Machine News Vol. 3, No 27, July 1905 (p. 111):

"For some months past the Columbia Co. have had record makers at work in China, securing both cylinder and disc records of Chinese comic and serious songs .... The latest list is of selections in the Pekinese dialect."

(source: Philip Yampolsky / Michael Kinnear)

These record makers must have been Charles W. Carson and Harry L. Marker.

It is possible that these recordings were conducted by Harry L. Marker and were the Hongkong recordings Heinrich Bumb referred to in Phonographische Zeitschrift 7 Jg./No. 32/p. 663:

"Geschäftlich fanden wir in Hongkong eine sehr starke amerikanische Konkurrenz vor.

Die Columbia Graphophone Co. hatte erst kürzlich in Hongkong ihre Neuaufnahmen, man sprach von 1000 Piecen und von Honoraren im Betrage von 50000 Dollar, beendet."

Bumb arrived in Hongkong on 18 Febr 1906.

Marker ("operator") left England on 15 July 1905 and arrived in New York on 22 July 1905 What was he doing in England?

Perhaps he was travelling "in transit" from China to the USA.

It is possible that the 1905 Hongkong recordings for some reason turned out a failure and had to be repeated in 1907.

(1)

Mid-1905 - 1907

Two and a half years in the Orient

Marker ("operator") left England on 15 July 1905 and arrived in New York on 22 July 1905 (What was he doing in England?).

On 16 October 1905 Harry Marker applied for a passport in New York

"[I do solemnly swear] .................... that I am about to go abroad temporarily and that I intend to return to the United States within two years..."

Presumably he travelled overland from New York to San Francisco.

Did he leave the USA for Japan via San Francisco? Very likely.

Began recording in Japan (Yokohama?)

Then went to China.

Stayed for a year in China (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai and Hongkong).

Harry L. Marker spent a year, from about May, 1907, in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Beijing and Tianjin. Part of the time he worked with Carson and part of the time he worked alone.

(Du Jun Min)

Around May [1907], he moved to Hong Kong to be an assistant to Harry L. Marker for a new recording session. Recordings made in this session were issued in a 57000 series with catalogue numbers ranging from 57700 to 578XX, and the labels had a golden Chinese dragon on a green background (Fig.14).

(Du Jun Min)

In 1907 he went from China to Singapore and Siam (Thailand) and returned to the USA via Europe.

His (first) wife Pearl Bessie may have accompanied him on his recording trip in view of the fact that Harry and Pearl Bessie Marker left Southampton on 20 Nov 1907 and arrived in New York on 26 Nov 1907.

Or was his wife waiting for him in England?

Harry L. Marker Back from Orient Where He Induced Oyama, Nogi and Ito to Give Homely Talks to Jap People, via the Graphophone - The Geisha Girls and Sing-Song Girls and Chinese Royal Actors as Record Makers - Working in Barn of Siamese King.

Over in Japan where the people, from Jinricksha men up, place the welfare of their country above mere personal comforts, the talking-machine is the greatest disseminator of patriotism. At least, the Japanese government officials, instructors of the young, warriors on land and sea, and even the great Mikado himself seem to think so.

And, believing this, the famous men of Japan have in the past three or four years done everything they could to help the graphophone along the path of prosperity and some of the most distinguished men in the Empire have made talking-machine records, which have a tremendous vogue in that land of kimono-clad people.

Harry L. Marker, who has just returned from a tour of the world, during which he stopped two and a half years in the Orient on a record making visit, talked interestingly of his experience this week to a reporter for THE MUSIC TRADES.

As the representative of the Columbia Phonograph Co. he established laboratories in many cities in the East.

From these laboratories come records made by Nogi, Oyama, Marquis Ito and many other of the great men of Japan, records that are now being heard by hundreds of thousands of Japs.

The talking-machine companies which do an export business have learned in their experience with the world's trade that the most obscure nations will gladly buy talking-machines if they can hear records made by their own people.

A South Sea cannibal would flee from a record of Caruso or Bonci or Melba, but will go almost insane with delight at hearing his own patois emerge from the horn of a machine. And, so, the companies send their own men, experts in record making, to every part of the globe and make sets of records for each country.

The best native talent is secured and the people are given the music and songs which they love best.

When Mr. Marker reached Tokio he found that the Columbia graphophone was remarkably strong with the people and he set about making records which would increase the demand for graphophones.

Knowing the patriotism of the Japanese people he determined to get phonographic messages from some of the greatest men in Japan.

Through influential Japs the plan was presented forcibly to the celebrities, who agreed to make the records.

They did so only under one condition, however, and that was that the records should not be sold outside of Japan. To this Mr. Marker readily agreed.

Records Made at Palaces of Celebrities.

It was arranged that he should call at the palaces of the celebrities and have the records made there.

Mr. Marker and an assistant took their apparatus to the homes of Marquis Ito, who is now Resident General in Corea, and one of the sages of the Empire; Nogi, who added to his fame by brilliant work in the field during the Russian-Japanese war [1904-1905]; Oyama, statesman, and others.

The palaces of the Japs are of ancient construction, and it was necessary for the Yankee workmen to tear down partitions in order to install their apparatus, old walls which had not been touched by the hand of mankind in decades.

The famous Japs regarded the process with interest and evidently were delighted with the idea of having their voices recorded.

When all was ready each gave a homely sermon to the people, made of platitudes that would endear the heart of a president of a republic. These words of wisdom, piety and lofty thought have since circulated from one end of the Sunny Kingdom to the other.

It was a fine coup for the Columbia. Mr. Marker says that the quality of tea and cigarettes served in the homes of the Japanese great is unusually excellent.

The principal of one largest young ladies' schools in the Empire, and the instructor of the children of the Empress, a man of considerable prestige in Tokio, was induced to make several records.

Every mother of ambition in Japan wants her daughter to hear the words of this great wise man, who has the ear of the Empress, and these records sell rapidly.

The best of the Japanese songs were sung for the graphophone by the leading actors and singers of the Empire.

And did the geisha-girls sing? Well, they certainly did.

And, Mr. Marker wants to go on record regarding these same geisha girls.

You know there is a prevailing impression among untraveled Americans that the geisha girls are nothing but dancers and tea servers and - well, you know.

That is entirely erroneous, Mr. Marker says.

They are skilled in the art of entertainment, fascinating in conversation, not too wise and not too demure, and they can discuss with equal facility policies of state with a minister of foreign affairs or the latest news of the "Bob" Evans' fleet with a mere Yankee Jack tar.

Now many of these geisha girls are wonderful actresses and others have voices such as Mr. Hammerstein and Mr. Conrad fight over in the courts.

They blushed demurely when led into the recording room and did their best in record making.

Every Jap gallant has his favorite geisha's voice à la Columbia graphophone always on hand. In Japan the machines are sold in many shops and there are even installment houses.

Going from Japan to China, Mr. Marker spent a year divided between Pekin, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Tien-tsin, the city that the Boxers held in July, 1900, and was relieved by the allied forces of Europe and America, who, after reaching the city and marching on to Pekin stole everything in sight.

Well, the Boxers have pretty much disappeared now but there is plenty of dirt.

And on the subject of Chinese dirt, Mr. Marker is eloquence itself.

When he got to Shanghai and started looking for a laboratory room he was able only to find one room in the city that was unoccupied.

The dirt and odor were something fierce.

Nothing could be done until a gang of coolie cleaners got to work with brooms and shovels and finally with a pail of whitewash. Eventually the place was given the semblance of cleanliness.

One of the first things that strike the foreigner when he gets traveling about the Chinese Empire is the lack of homogeneity.

This is particularly noticeable in the languages.

There is the Pekin dialect and the Canton dialect and so many others that only a skilled linguist can distinguish them. It would not be so bad but the residents of one province can't understand those of another, so in making talking-machine records it is necessary to have actors in all the dialects of the province where the goods are to be sold.

The language of the Pekin court - the mandarin dialect - is used by the aristocrats all over the Empire, but it can't be understood by the poorer people.

When Mr. Marker got to Hong-Kong he had to send over to Canton for a troupe of actors and musicians to make records. They came - about seventy of them.

There were gong players - and banjoists, sing-song girls and baritones and they all camped out in Hong Kong at the expense of the Columbia Phonograph Co., which not only had to pay their transportation but their cost of living while in Pekin.

The expense bills they sent in were corkers, including everything from tiffin and chop sticks to san suey, Chinese rice, wine, shark fins and - keep this secret, opium.

Of course, the talking-machine companies do not favor the use of opium, but if the actors insist upon smoking it and won't sing until they get it, what is the talking-machine company to do but buy the dope?

Records of Oriental Singers and Actors

Mr. Marker and his assistants had records made for the Columbia by the great actors of the Empire and some of the most famous of the sing-song girls, who, by the way, are in many instances extremely pretty and in all instances remarkably chic.

Some of the actors who sang for the phonograph are men who appear before the Emperor only.

How the Columbia Company secured their services is a feat which the export department of the company is not divulging.

China has the oldest opera in the world, the weirdest scenically and the longest. It is not unusual for a performance to last anywhere from three to five months.

The natives inured to all sorts of torture, including the bastinado, go night after night and seem to shrive on it.

They listen to operas which were written centuries ago. The singers learn their roles from infancy and do not use notes.

When Mr. Marker learned that the operas ran easily along for more months [did he perhaps mean "days"? "Die Aufführung einer vollständigen Oper konnte durchaus mehrere Tage in Anspruch"] than the talking-machine record does minutes, he naturally was rather perplexed to know how he was going to get that music on the graphophone. It is there all right.

Native experts decide just what are the chefs d'oeuvre of these "operas" and the singers render these selections. The music sounds pretty much all alike to the American. The Chinese music is noisy, with the gong playing an important part.

The gong player is a man with an iron wrist, who, after years of service, does not need cotton in his ears.

He is playing most of the time, but must never hit the wrong note.

The banjo players have our minstrels of a former generation beaten.

Many of the singers have unusually fine baritone voices.

The soprano of the sing-song girls would strike the average American as shrill. It is a sort of long drawn out shriek that strikes terror to the foreign ear, but gives unending delight to the natives.

The Chinese insist that each instrument in the "band" be heard when it is reproduced by graphophone.

Now, this is easier said than done. Endless experiment is necessary to achieve the exact effect.

The Chinese actors like to sing for the talking-machine for they are well paid and the sale of their records increases their popularity. Some of the singers who came to the Chinese laboratories established by the Columbia company traveled miles to get there. Despite the affection for the folk-songs the Chinese people welcome new compositions, and Pekin, Tien-Tsin and other cities have small armies of native composers, all trying to outdo the efforts of the ancients. Occasionally, something popular is written. The joy of some Chinese villagers miles in the interior at the privilege of hearing in their homes songs sung in Pekin theatres - and by favorites of the Emperor at that - can be readily appreciated.

The popularity of the talking-machines in China is something amazing: from the mandarins down to the coolies the graphophone is found everywhere. It greets one on the century-old streets of Pekin and in the wilds of Manchuria.

While in China Mr. Marker was given a dinner by a company of Chinese actors who were singing for the Columbia Phonograph Co.

Mr. Marker never attended anything like it in his experience and probably never will again. There were forty-two courses in all, with san suey between courses. After eating for two hours Mr. Marker thought that the limit had been reached, but all hands quit the table, smoked some, drank some more san suey, and getting a fresh grip on their appetites started in again. Mr. Marker quit the table and decided never to eat again.

On the following day he was ready to again listen to the call of the dinner gong.

From China Mr. Marker went to Singapore and Siam. There more native talent was coralled. In Siam he made records in the barn attached to the King's Palace.

It was not a tin roof, red painted, Kansas-like barn, but more like a tremendous fairy palace. He returned home by way of Europe, completing the circuit of the globe.

(source: Making Columbia Records in Famous Jap Places (in: The Music Trades, 4.1.1908: 38.)

HARRY L. MARKER BACK FROM INDIA

Harry L. Marker, on the laboratory staff of the Columbia Phonograph Co. General, who recently returned from making records in India [correct? - HS], will leave for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, January 20. His work will be confined solely to that country, and he proposes visiting every town of any size in that vast territory to obtain native talent for both music and talking machine records. Mr. Marker may be away a couple of years.

(from: The Talking Machine World, Vol. 4, No. 1 of 15 Jan 1908 (p. 36)

On 18 March 1908 Harry and wife Pearl Bessie Marker left the harbour of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on board of the SS "VERDI".

They arrived in New York on 6 March 1908.

Presumably Marker made recordings for Columbia in Brazil.....

Henry MARKER (35y = 31y) engineer

+ G. MARKER (27y) wife (should be: P. MARKER)

+ Charles W. CARSON (36y) engineer

SS "VERDI"

18 March 1908, Rio de Janeiro, BRAZIL

6 April 1908, New York

residence: Newark, NJ

On 29 October 1908 Harry Marker together with his wife Pearl Bessie and colleague William F. Freiberg departed from Vera Cruz, Mexico, on board of the SS "MORRO CASTLE", where he must have been making recordings for Columbia.

On 7 November 1908 they arrived at New York.

Not in 1910 CENSUS (started on 15 April 1910), because Harry and his wife were in the Far East, making recordings).

They returned to USA (San Francisco) in Sept 1910 (ship left Hongkong on 27 Aug 1910)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Harry's parents are in the 1910 census (29 Apr 1910, Newark, Essex, NJ):

Stephen A. Marker (62y) leather worker tannery

Colombia (sic) Marker (52y)

On 27 Aug 1910 Harry and his wife Pearl Bessie Marker left Hongkong.

They arrived back at San Francisco on 23 September 1910.

Where along the way did they get on board?

1912 recording in Far East for the Columbia Phonograph Company.

Singapore - Shanghai - Port Arthur - Trans-Siberian Railway - German border - England - New York

BESET ON LONG HOME TRIP

Twice in Hospital and Also Quarantined Getting Here for Christmas.

ORANGE, N. J. Dec 25 [1912].-

Journeying virtually "from the ends of the earth," Harry L. Marker of 7 New England Terrace, Orange, got home today to spend Christmas with his wife and family.

Mr. Marker's homeward trip was full of vicissitudes, and it looked more than once as if the Yuletide would come and go while he was still on the way.

He spent five weeks in two hospitals as the result of accidents.

Luck was with him at the end, however, and he landed at New York yesterday on the George Washington from Liverpool, with only a few hours to spare to get home before Christmas Eve dissolved into Christmas morning.

Mr. Marker was getting phonograph records of the Far East for a phonograph company, and he set out to spend Christmas at home some months ago. He was then in Singapore.

Just before sailing he strained his side and had to go to a hospital for a month.

After he got started he was the victim of an oil lamp explosion at Shanghai, which put him in the hospital another week with burns.

For six days he was quarantined at Port Arthur as a cholera suspect.

He finally got away, via the Trans-Siberian Railway, but at the German frontier was delayed four days by lost trunks.

That was enough to cause him to miss the Lusitania.

He finally got to England in a rush for the George Washington, his last chance.

(source: New York Times, 26 Dec 1912)

Harry MARKER (36y)

SS "GEORGE WASHINGTON"

15 Dec 1912, Southampton, ENGLAND

24 Dec 1912, New York

RETURNS FROM RECORD MAKING TRIP AROUND WORLD

An Interesting Story of Henry L. Markers Trip and Accomplishments in Hawaii, Singapore, Java, Hong Kong, Shanghai - Some Odd Experiences In Making Records - Many Difficulties Encountered, but the Winning Man Conquers - Java a Country That Delights the Student of People and Happenings - How Marker Managed to Secure a Photograph of a Procession In Which Three Sons of the Sultan of Java Participated.

On Christmas eve, 1912, Harry L. Marker, Columbia recording expert, boarded a train in the Jersey City station of the Lackawanna railroad and made the last lap of a 12,500-mile hike that brought him home to Orange, N. J., just in time to celebrate Yuletide. He had left China nearly two months before and traveled west - the Trans-Siberian railroad across Siberia and Russia; on through Germany, after an argument with the customs officials, a stop-over in London while awaiting some baggage that had gone astray in the middle of Europe; and then the North Atlantic trip.

Harry L. Marker left New York in April 1911. Victor H. Emerson, superintendent of the Columbia Recording Laboratory, started with him. The two stopped over in Salt Lake City, Utah, and put in some experimental work and then traveled together as far as Frisco.

Here they parted. Mr. Emerson stayed a while in San Francisco, his birthplace [?], and Mr. Marker kept going west.

His first stopping-place after leaving this country was Honolulu, and the result of his visit there materialized in the wonderful series of Hawaiian records that the Columbia Phonograph Co. has since put on the market. Some of them have been listed domestically for home consumption, and are proving very popular.

But the records had nothing on Marker, for in Hawaii he made himself just as popular as the records have become in America, and the oldest inhabitant of Honolulu will tell you that there never was such a triumphal exit from that fair and beautiful island as that made by Harry L. Marker. Hawaiian royalty turned out for the occasion and, led by princesses of royal blood, with native bands and singers, the Harry L. Marker farewell to Honolulu was a tremendously impressive and picturesque occasion. Mr. Marker himself, the center of all the proceedings, was easily the most picturesque figure there, with floral decorations and wreaths and festoons of flowers and garlands of green stuff draped around his manly chest and shoulders. The latter he flung back onto the surface of the waters in token that he returned the good-will of his hospitable hosts.

From Hawaii Mr. Marker went to Singapore. In Singapore he found John Dorian, the Columbia Phonograph Co.s Oriental representative, in the hospital. Mr. Dorian had gone down with fever and dysentery in Siam and had journeyed by gradual stages to Singapore, where he could get better medical treatment. He recovered his health in some measure and the two traveled together to Batavia, Java, where the Columbia contract was made with Tio Tek Hong, and where Mr. Marker made over five hundred records. It is quite possible that those Javanese records might not appeal to the cultured musical taste of America and Europe, but over in Batavia they are reckoned great stuff. Most of them are native music pure and simple, but among them are adaptations from Broadway. There is one in particular - a record of After the Ball - sung in Javanese and accompanied by the Javanese idea of what an accompaniment ought to be. The orchestra included a piano, a clarinet and two fiddles - the clarinet and two fiddles in accordance with local ideas as to what ought to be clarinets and fiddles. The most typical instrument of native music throughout Java is the gamalong [sic - HS]. It looks like twenty-four different kinds of drums and sounds like a medieval xylophone in a straitjacket. Mr. Marker succeeded in getting a very fine series of gamalong records, both with the instrument in solo and also as an accompaniment. The favorite diversion of the wealthy Javanese is to get some star vocalist who can sing and play his or her own accompaniment on the gamalong. Mr. Marker got hold of one lady who, according to all reports, was the local Tetrazzini, only more so. At the time appointed for the securing of records the dusky diva made her appearance with a retinue of coolies carrying the various component parts of the gamalong. These she set out in battle array, so to speak, and at the word go from Mr. Marker she opened up hostilities.

Mr. Marker personally had his troubles, but they were counterbalanced by a good many very enjoyable recollections. Not the least of these was the assistance and general good treatment he received from E. S. Reardon, American consul in Batavia, and B. Powell, an Englishman, who is the American consular agent in Soerabaya. Both of these were men of fine caliber and just the right type for the work they have to do out there - brainy enterprising diplomats. The latter, Mr. Powell, gave Mr. Marker two or three days shooting on his country estate up in the hills, and the Columbia recording experts bag included three lions and a couple of panthers, besides wild fowl..

A lot of Arabian and Chinese records were secured in Soerabaya, and then Mr. Marker went on to Singapore for L. E. Salomonson for Malay and Chinese records. In Singapore, after a good deal of investigation through the native quarters, Mr. Marker satisfied himself that he had the best native band there was in the city, and the usual appointment was made for them to play into the recording machine.

Mr. Marker, be it known, in a pith helmet and a suit of white duck, with shoes to match, is an imposing figure. Wherever he went he made a great impression on the natives; in fact, in one place he had a whole regiment of them praying to him. This Malay band in Singapore was no exception to the rule, and they decided that if they were going to play for the big white sahib it was up to them to put on their best bib and tucker, so to speak. They did, and it was a gorgeous sartorial kaleidoscope that presented itself at the temporary recording department - fourteen of them actually wearing trousers and boots. After the first selections had been made, however, Mr. Marker noticed that the band did not seem quite comfortable, and then a bright idea struck him and he said to the interpreter: Tell that bunch of misguided heathens to take off their boots or there will be no more records made. The boots came off, they stretched their toes and wiggled them with a keen degree of comfort, and the balance of the record-making session was a success.

It was Java that yielded up the biggest homage to Mr. Markers white suit, for it was there that Mr. Marker stage managed a royal pageant until he had it to his own liking. One day while Mr. Marker was staying in Djokjokarta, the capital of middle Java, the three sons of the Sultan of Java were to be initiated into certain mysteries of the court, and the event was celebrated with true Oriental pageantry. There were musicians and dancers and all sorts of court functionaries in the procession which followed the ceremony. Marker was looking on, and it struck him that a really good photograph of the scene would be a fitting souvenir. When his interpreter was told what he wanted, he [= the interpreter] was scared to the verge of paralysis, but managed to collect his wits enough to run away, so Marker fell back on an ancient Dutchman, who spoke the native language. He told him what he wanted. Sure thing, said the Dutchman, or words to that effect. Come along. So they held up the procession and they grouped the princes and functionaries and the musicians and soldiers into just the kind of pose they wanted; then they borrowed a couple of the soldiers to keep the rest of the crowd away and Marker took his picture, said Thank you, and the procession went on - in proof of which we reproduce the photo - and each of the three umbrellas indicates a prince.

Marker had a close call in Singapore. He was using gasoline for illuminating purposes and the climate was so hot at that season of the year that it exploded and Marker caught fire. Had it not been for the devotion of his Javanese assistant, whom he had taken along with him from Soerabaya, Marker would never have come back to New York. The Javanese first of all put out the flames that enveloped Marker - although not before he was badly burned - and then with three or four volunteers managed to save his instruments before the building burned down.

From Singapore Marker went on to Hong Kong for Chinese records and was aided considerably by Mr. Fong-Foom. A building was hired in the city and the recording plant installed; then Marker looked around for a watchman. He engaged one, but when Watch saw the building he salaamed very profusely, and said: Me no sabee want um job; no can do. That was all he said, but he said it over about ten times and lived up to it. He simply refused to go inside the house and Marker started to investigate the trouble. He went to the owner. The owner, of course was Oriental, folded his hands across where his waist line ought to have been, and said: Me velly solly; eight people die one week - plague. With a few days to spare after making his Hong Kong records, Marker accepted the invitation to visit Fong-Fooms home up the West River. A crew of women paddled him up the river in a dugout until they came to a place where Fong was making ramee cloth. There were a couple of hundred or so coolies working in the ramee field; and one of them when he came down toward Marker accosted him in perfectly good English: Hello; where are you from? As there wasnt a white man living within fifty miles of that place, Marker was considerably startled. New York, said he. You sabe know New York? Bet cher life, said the coolie in the most approved Bowery accent. I ran a joint in Third avenue for eleven years.

Shanghai was Markers next stop and here a contract was made with the firm Mustard & Co. A further set of Chinese records was secured and John Dorian, whose health at this time had broken down, left Marker and sailed for San Francisco.

Marker took a train on the Trans-Siberian for New York; was held up as a cholera suspect; his baggage was sent astray; he nearly became a prisoner in a military fortress because somebody thought he looked like a spy; he had a very hot argument with German customs people because he hadnt brought his baggage with him, and finally was held up in London for a week until the baggage did turn up. After all of which, as we said in the beginning, he made Orange, N. J., on Christmas eve, and achieved what he intended to do when he left China - spend Christmas day with his wife.

(source: The Talking Machine World Vol. 9, No. 1, of 15 Feb 1913, pp. 43-44)

With the article come 7 photos with the following captions

Photo 1 H. L. Marker

Photo 2 H. L. Markers Laundresses at Work

Photo 3 State Procession at Java (Royal Princes Under Umbrellas)

Photo 4 Native Band of Batavia on Way to Make Records

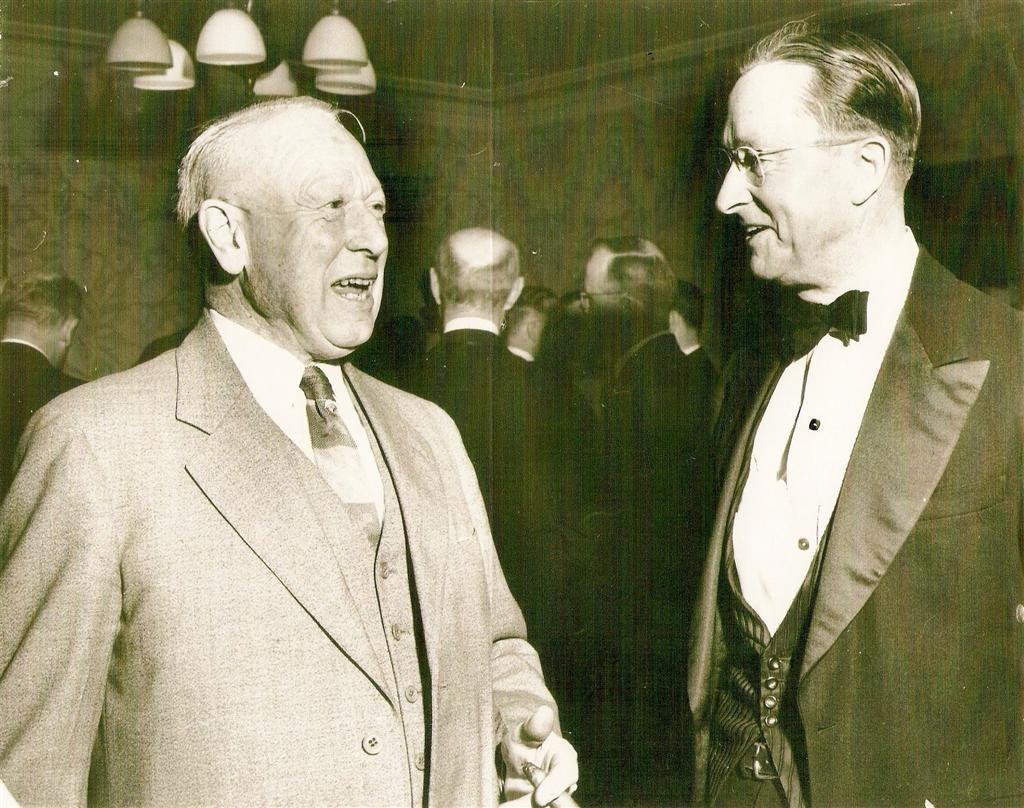

Photo 5 John Dorian on Left - H. L. Marker on Right

Photo 6 Victor H. Emerson

Photo 7 H. L. Marker Dancing in Java to Native Music

These photographs - in theory tantalizing material - cannot be reproduced here owing to the fact that they were copied from a very bad original.

John H. Dorian accompanied Harry/Henry L. Marker on his 1911-1912 Asian trip for Columbia Phonograph Co. General

(source: Returns from Record Making Trip Around World (in: The Talking Machine World 9, no. 1, 15 Feb 1913, pp. 43-44)

While Harry Marker returned to the USA via Europe, John Dorian took the route across the Pacific Ocean to San Francisco. Dorian - very sick - never reached the USA: he died at Honolulu, Hawaii, on 14 November 1912.

John H. DORIAN (name deleted)

SS NIPPON MARU

29 Oct 1912, Hong Kong, CHINA

1 Nov 1912, Shanghai, CHINA (port of embarkation)

3 Nov 1912, Nagasaki, JAPAN

5 Nov 1912, Kobe, JAPAN

9 Nov 1912, Yokohama, JAPAN

24 Nov 1912 died at age 45 in Honolulu, HAWAII

25 Nov 1912 ship arrives at San Francisco, CA

WWI 1917/1918 Draft Registration Cards

Harry Louis Marker

221 Grove Rd. South Orange, Essex, NJ

born: 21 June 1876

Recording Engineer Emerson Phonograph Co.

358 5th Ave, New York, NY, NY

Mrs. Pearl B. Marker

Color of hair: red

Color of eyes: grey

(Sept 1918)

1915-1921 recording engineer EMERSON PHONOGRAPH COMPANY, NY

Marker retired in 1925 (1930 according to newspaper clipping).

Marker must have remarried: Louise ........

However, she must have died prior to Harry, since she was not mentioned in Harry's obituary.

EARLY PHONOGRAPH RECORDING ENGINEER RECALLS WORK ABROAD

Traveled 250.000 Miles Making Records of Native Music in Foreign Countries

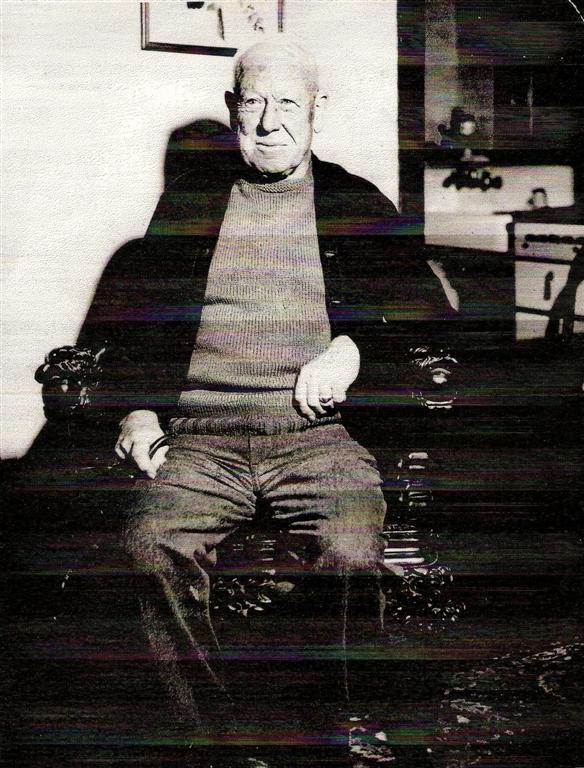

One of the pioneer engineers in the phonograph recording business is Harry L. Marker of 27 Summit street, Newark, who will observe his 70th birthday June 1922.

He retired in 1930 as superintendent of the Emerson Phonograph Company when he was earning $20.000 a year.

"What's the use of piling up all that money when all you have is one mouth to feed and all you need is one suit of clothes to wear?" remarked Mr. Marker yesterday.

"That's the question I asked myself; then I retired."

But before he left the recording industry to take things easy at his summer home in Lake Hopatcong and "just fish," Mr. Marker traveled around the world three times, made four trips to South America and five to China - more than 250.000 miles - making foreign records for the Columbia Phonograph Company, now the Columbia Recording Company.

25 Years in Business

Mr. Marker was in the recording business 25 years. Fifteen of his 20 years with Columbia were as foreign engineer in complete charge of all recordings made for that company in China, South America, Japan, Malay, Siam, Java, Cuba and the Philippines.

After graduating from Rutgers University in 1899, Mr. Marker took a job as clerk with the Prudential Insurance Company. He left the firm to go with Columbia.

"No, I wasn't born in Newark," Mr. Marker said. "I'm a Hoosier, a native of Indianapolis. But I've lived here 60 years."

Mr. Marker said there was "a tremendous profit" in the foreign record field.

"In those days, natives of the countries where we set up our temporary laboratories wanted records of their songs, their bands and story tellers," he said. "We made the wax original and shipped it back to our factory in Bridgeport. The records were made there and sent back to the country for selling."

Mr. Marker's feeling for the Japs is tinged with bitterness. Conversely, he regards the Chinese as kindly, honest people. He has personal reasons for both emotions.

Japs copied outfit

"I knew the Japs so well that I could have predicted 20 years ago that we would be at war with them," he explained.

His opinion of the Japs was formed on his first trip to that country. His laboratory, used for pressing and plating records, and recording outfit were copied by the Japanese, who then made their own machine, forcing Mr. Marker out of the business in Japan.

"They used to come in the room where the laboratory was set up and make diagrams of the equipment," Mr. Marker said. "You must remember it was the time when recording companies kept their trade secrets to themselves. There were only two major companies at the time.

I had a hunch that the Japs were sneaking in the room at night. My suspicion was confirmed one morning when I noticed that a string I had attached to two gears were (=was) broken. I had fixed the string so that it would snap if the turntable was moved an eighth of an inch."

Others Think Our Music Weird

While he was concerned only with the mechanical end of recording, Mr. Marker assimilated much of the customs, folklore and music of the countries he worked in.

"The music of the Chinese and Japanese, to our ears, is weird," he said. "They think the same of our music. The Chinese have only a five-note scale. This makes their music sound very monotonous. There is very little in the Malay music. It's not much; they vocalize in a sing-song fashion. They don't have any grammar, you know, and they sing anything they please."

Regarding the present rage for South American music, Mr. Marker chuckled: "Why we had all that stuff years ago. We sold all those records in South America. The American people did not think anything of it then."

In China Mr. Marker's standard equipment included an opium bunk, which was set up before the laboratory. The Chinese entertainers would take a smoke before making a record.

Once when a Chinese performer, regarded as the best male singer in that country, balked at making a record because he could not hear a playback. Mr. Marker took a few puffs to appease the singer. The singer thought it was very funny. He made the record - for $500. Mr. Marker didn't think the price was funny.

Days of Trial and Error

At 70, Mr. Marker has blue eyes that twinkle in a seamed face. His hair, flaming red in his youth, is sparse and white. He has a good memory, recalling incidents in a lucid, unhesitant manner. He has kept in touch, too, with progress in the recording industry since his retirement.

"The work today is so much different," he said. "Where we did all our work with the horn, all acoustical, today it is all electrical.

They can get anything at all. We couldn't take a bass fiddle - the swing was too big. But with the new instruments, all of them calibrated, they have no trouble. In the old days it was trial and error. We had to make our own instruments."

But there was this feature in the old days, Mr. Marker recalled, that doesn't exist to a large degree today: "We were specialists, and they could not go out and get someone else. And after you served your apprenticeship you were in the big money."

That's why he's able to take things easy and just fish these days.

(from: unknown newspaper article, .........., .. June 1946)

Marker had a summerhome at Lake Hopatkong.

Harry Louis Marker died on 21 March 1966 at the East Orange Veterans Hospital, Newark, New Jersey.

He was buried at .............

_____________________________________________________________________________

WWI Draft Registration Cards 1917-1918:

Harry Louis Marker

born: 21 June 1876

color of hair: red

color of eyes: grey

Recording Engineer Emerson Phonograph Company, 358 5th Ave, New York

Pearl B. MARKER, 221 Grove Road, South Orange, Essex, NJ

(Sept 1918)

Harry L. MARKER (27y)

SS "MONTEREY"

21 Jan 1904 Vera Cruz, MEXICO

31 Jan 1904 New York

Harry L. MARKER (29y) operator

SS "CAMPANIA"

15 July 1905, Liverpool, ENGLAND

22 July 1905, New York

Passport Application dated 16 Oct 1905:

I intend to return to the United States within two years.

Henry Louis MARKER (31y) engineer

+ Pearl Bessie MARKER (26y)

SS "KRONPRINZ WILHELM"

20 Nov 1907, Southampton, ENGLAND

26 Nov 1907, New York

Harry L. MARKER (31y)

+ Pearl B. MARKER (26y)

+ William FREIBERG (30y)

SS "MORRO CASTLE"

29 Oct 1908, Vera Cruz, MEXICO

7 Nov 1908, New York

Harry MARKER

SS ".........."

dep.: 23 Nov 1909, San Francisco

arr.: ....... 1909, ......., CHINA

Harry L. MARKER (34y)

+ Pearl B. MARKER (29y)

SS "CHINYO MARU"

27 Aug 1910, Hong Kong, CHINA

29 Aug 1910, Keelung

31 Aug 1910, Shanghai

2 Sept 1910, Nagasaki, JAPAN

4 Sept 1910, Kobe

6 Sept 1910, Yokkaichi

8 Sept 1910, Yokohama

23 Sept 1910, San Francisco

residence: Orange, New Jersey

Harry MARKER (36y)

SS "GEORGE WASHINGTON"

15 Dec 1912, Southampton, ENGLAND

24 Dec 1912, New York

residence: 7 New England Terrace, Orange, NJ

born: 21 June 1876, New York (a mistake?)

Harry Louis MARKER (52y) engineer

SS "AQUITANIA"

... May 1928, New York

2 June 1928, Southampton, ENGLAND

202 Marylebone Road

Harry Louis MARKER (52y)

SS "AQUITANIA"

11 Aug 1928, Southampton, ENGLAND

17 Aug 1928, New York

residence: 27 Summit St., Newark, NJ

born: 21 June 1876, Indianapolis, Indiana

NOTES

- Conversations/Correspondence with Christian Müller

- Zwischen Unterhaltung und Revolution. Grammophone Schallplatten und die Anfänge der Musikindustrie in Shanghai 1878-1937 by Andreas Steen (Harassowitz Verlag - Wiesbaden, 2006)

- Conversations/Correspondence with Mrs. E. R. Yeaton

- article from unknown newspaper (undated; June 1946) probably from New Jersey area

- Obituary

- RETURNS FROM RECORD MAKING TRIP AROUND WORLD (in: The Talking Machine World Vol. 9, No. 1 of 15 Feb 1913 (pp. 43-44))

- WWI 1917/1918 Draft Registration Cards

- The Talking Machine News Vol. 3, No 27 of July 1905 (p. 111))

- Passport Application of 16 October 1905 (New York)

- Making Columbia Records in Famous Jap Places (in: The Music Trades, 4.1.1908: 38.)

- U.S. City Directories, Hartford, Connecticut: 1877, 1880 and 1881

- 1912 recording in Far East for the Columbia Phonograph Company.

Singapore - Shanghai - Port Arthur - Trans-Siberian Railway - German border - England - New York

- BESET ON LONG HOME TRIP

Twice in Hospital and Also Quarantined Getting Here for Christmas.

ORANGE, N. J. Dec 25 [1912].-

(in: The New York Times of 26 Dec 1912)

- Passenger lists

- Federal Censuses

- The Development of Chinese Records from the Qing Dynasty to 1918 (article by Du Jun Min (Buenos Aires, Argentina) on website: Antique Phonograph News (Canadian Antique Phonograph Society))

- Phonographische Zeitschrift .............

- Round the World with a "Talker" (in: The Talking Machine News No. 5 (72), p. 773 of 15 Feb 1908)

- Around the World with a "Talker" (in: The Talking Machine World Vol. 6, No. 12 of 15 Dec 1910 (pp. 49-50))

- Harry L. Marker back from India (in: The Talking Machine World, Vol. 4, No. 1 of 15 Jan 1908 (p. 36))

- Developing our Export Trade (in: The Talking Machine World, Vol. 4, No. 2 of 15 Feb 1908 (p. 18-20))

- Walter (= William) Freiberg and Harry L. Marker return from Mexico (in: The Talking Machine World, Vol. 4, No. 11 of 15 Nov 1908 (p. 59))

- Marker off to the Orient (in: The Talking Machine World, Vol. 5, No. 12 of 15 Dec 1909 (p. 28)

COMPANIES & LABELS

COLUMBIA (USA)

COLUMBIA GRAPHOPHONE COMPANY (USA)

COLUMBIA PHONOGRAPH COMPANY

EMERSON PHONOGRAPH COMPANY

SPEAK-O-PHONE

THANK YOU

Elizabeth Rea Yeaton

Christian Müller

Philip Yampolsky

Evelyn Huey (RAOGK)

Kathy Meagher

Matthew Gorham

Sue

Diane Barlow